Unit 7 – Current Problems in American Ocean Management: Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing

Current Problems in American Ocean Management

Contents

Introduction

Enforcement

High Seas Task Force

Introduction

In Unit 5, we looked at examples of how law deals with some contemporary, urgent ocean impacts. Unit 6 shed light on how international fisheries are managed. Unit 6 will provide an overview of tools available to confront the major, complex and serious global problem of illegal fishing. The purpose of this unit is to set the stage by providing an introduction and overview to IUU fishing.

Estimates of IUU fishing vary from 15-30% of global catch, robbing the poorest coastal nations of upwards of $1 billion annually. The drivers include high seafood demand, high profits with lower perceived risks in the context of a product that historically defied detection of illegality. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, FAO defines IUU here.

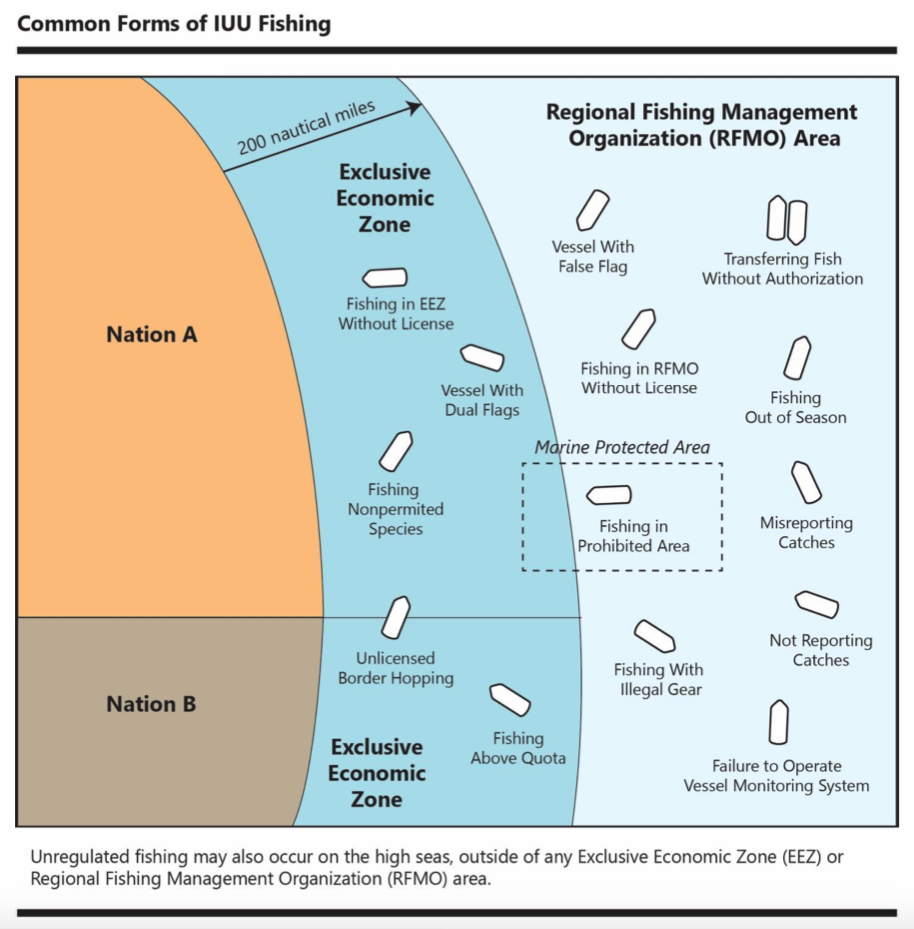

Illegal fishing refers to activities:

Conducted by national or foreign vessels in waters under the jurisdiction of a state, without the permission of that state, or in contravention of its laws and regulations;

Conducted by vessels flying the flag of states that are parties to a relevant regional fisheries management organization but operate in contravention of the conservation and management measures adopted by that organization and by which the States are bound, or relevant provisions of the applicable international law; or in violation

of national laws or international obligations, including those undertaken by cooperating states to a relevant regional fisheries management organization.

Unreported fishing refers to fishing activities:

Which have not been reported, or have been misreported, to the relevant national authority, in contravention of national laws and regulations; or activities

undertaken in the area of competence of a relevant Regional Fisheries Management Organization (RFMO), which have not been reported or have been misreported, in contravention of the reporting procedures of that organization.

Unregulated fishing refers to fishing activities:

In the area of application of a relevant RFMO that are conducted by vessels without nationality, or by those flying the flag of a state not party to that organization, or by a fishing entity, in a manner that is not consistent with or contravenes the conservation and management measures of that Organization; or in areas or for fish stocks in relation to which there are no applicable conservation or management measures and where such fishing activities are conducted in a manner inconsistent with State responsibilities for the conservation of living marine resources under international law.

The topic of IUU is constantly evolving. Governments, grassroots nonprofits, and even celebrities are becoming more involved (if you are intrigued, check out Global Fishing Watch, founded by Leonardo DiCaprio and Google http://globalfishingwatch.org).

As a beginning point, the 2006 reauthorizations to the Magnuson Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act included much-needed attention to stocks outside US waters. The reauthorizations provide the Commerce Secretary with the ability to monitor high seas fisheries, including stocks that are subject to international agreements and governing bodies. The 2006 updates initiated a suite of powerful improvements in international monitoring and information sharing, communication between enforcement agencies, and registry for vessels. The reauthorization established a process for the US to identify and then work with specific nations that have lax fisheries enforcement. Those countries may then take action to achieve greater compliance, and if successful then receive “certification” of their fisheries by the US.

To read the text of the MSA section on Illegal, Unregulated or Unreported (IUU) Fishing, go to 16 USC § 1826j):https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/16/1826j

For more about the strengthening of MSA’s enforcement provisions, explore here.

In conjunction with the 2006 MSA changes, the US focused on achieving greater cooperation with other nations through strengthening the Moratorium Protection Act (16 USC 1826d-k). The Secretary of Commerce reports progress to Congress every two years about consultations with countries with vessel offenses. The Moratorium Protection Act also provides for the Secretary, along with the Secretary of State and regional councils to undertake actions to improve international fisheries management. Within the organizations in which the US is a member, the US is authorized to urge regional fisheries organizations to do any of the following:

- Incorporate multilateral market-related measures against member or non-member governments whose vessels engage in IUU fishing.

- Seek adoption of lists that identify fishing vessels and vessel owners engaged in IUU fishing.

- Seek adoption of a centralized vessel monitoring system (VMS).

- Increase use of observers and technologies to monitor compliance with conservation and management measures.

- Seek adoption of stronger port State controls in all nations.

- Adopt shark conservation measures, including measures to prohibit removal of any of the fins of a shark (including the tail) and discarding the carcass of the shark at sea.

- Adopt and expand the use of market-related measures to combat IUU fishing, including import prohibitions, landing restrictions, and catch documentation schemes (CDSs).

The MSA definition of IUU fishing 16 USC 1826j(e)2(A-C):

(A) fishing activities that violate conservation and management measures required under an international fishery management agreement to which the United States is a party, including catch limits or quotas, capacity restrictions, bycatch reduction requirements, and shark conservation measures;

(B) overfishing of fish stocks shared by the United States, for which there are no applicable international conservation or management measures or in areas with no applicable international fishery management organization or agreement, that has adverse impacts on such stocks; and

(C) fishing activity that has an adverse impact on seamounts, hydrothermal vents, and cold water corals located beyond national jurisdiction, for which there are no applicable conservation or management measures or in areas with no applicable international fishery management organization or agreement.

Very relevant is the Secretary of Commerce’s duty to encourage other nations to adopt measures to prevent trade in fish products taken through IUU practices, bringing in important market forces relevant to traceability (putting systems in place at each step of the custody or supply chain that identify the fish in commerce from ocean to table).

According to Lewis and others (2017) seafood traceability is expanding as a tool to confront estimated IUU fishing losses of $10 to $23.5 billion per year (11 to 26 million tons, citing Agnew et al. 2009). As of January 2018, the new Seafood Import Monitoring Program will intercept at-risk seafood entering the US (see fisheries.noaa.gov/topic/international-affairs). The Monitoring Program will focus on eleven priority species: Atlantic and Pacific Cod, blue crab, mahi mahi, grouper, king crab, sea cucumbers, red snapper, sharks, swordfish and tunas. The monitoring will expand to shrimp, abalone and other species in the future.

Trade-related environmental measures (TREMs) can be more successful if accompanied by planning that begins with diplomacy and possible aid, and emphasizes a collaborative approach. Other tools used to combat IUU fishing have included prohibitions on landing, catch documentation requirements, import permits, direct bans on imports, and mandatory labeling schemes. For an example of traceability efforts, check out Fish Tracker Initiative that seeks to “align capital markets with sustainable fisheries management.”

The 2015 and 2017 Reports to Congress provide details about the accomplishments of the previous two years with regard to IUU fishing, bycatch (including seabirds), and shark conservation: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/international-affairs/identification-iuu-fishing-activities#magnuson-stevens-reauthorization-act-biennial-reports-to-congress

An interesting international case example of efforts to reduce IUU fishing in the Patagonian Toothfishery off Chile, is available at the site from the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR). CCAMLR’s conservation, licensing and enforcement program has had some success in reducing IUU fishing in this high-value fishery.

In addition to threatening an important supply of protein for the 4.3 billion people who depend on subsistence fisheries, IUU fishing also engages in devastating practices that include the use of dynamite, kerosene or fertilizer (“blast fishing”) or cyanide fishing, or gear that damages or destroys crucial habitats such as reefs. It is thought that IUU fishing disproportionately affects poor coastal communities.

In some cases, IUU fishing is directly linked to organized crime, with an unquantified portion tied to corruption (bribery of officials for example). In untold human cost, IUU often features forced labor, and is linked to human trafficking/slavery. IUU is known to contribute to piracy.

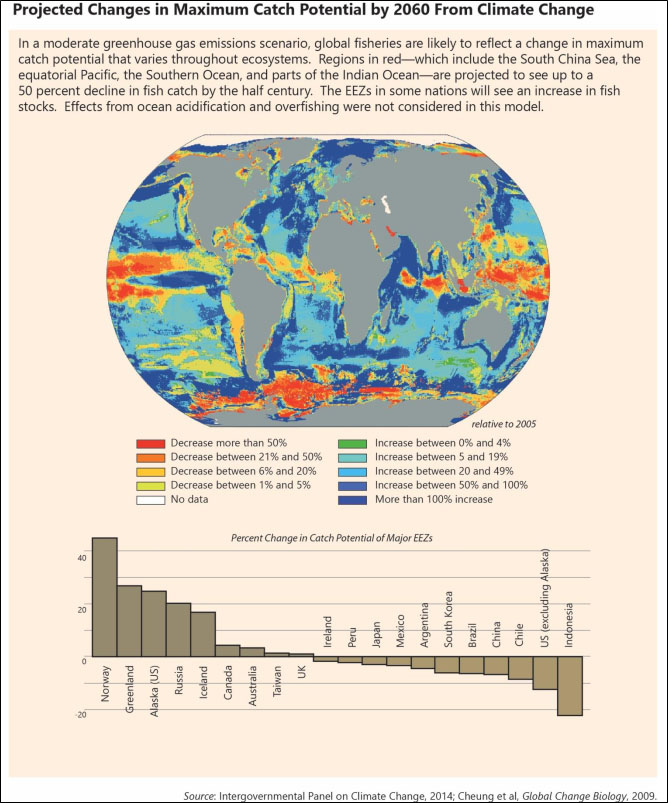

Finally, observers agree that climate change effects will reduce catch potential, captured in this graphic from IPCC (2014). The areas the most vulnerable reflect poor coastal countries (including Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius, Seychelles) that rely on subsistence fishing. The following graphic illustrates potential changes in catch by 2060.

Enforcement

Enforcement on the high seas is challenging because of the vast area to be patrolled. Under UNCLOS, Coastal States are responsible for vessels flying their flag. However, while the vessels themselves are liable, the contours of flag State liability are ambiguous. A 2015 Advisory Opinion from the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) found that flag States must exercise due diligence. Closer to shore, coastal states must prevent IUU fishing. In international waters (beyond 200 nm) flag States have only general responsibilities to ensure normal regulation of vessels, compliance with applicable treaties, and adherence to best practices.

High Seas Task Force

In 2006, a task force made up of NGOs (World Wildlife Fund, International Union for the Conservation of Nature, and Columbia University’s Earth Institute) and government representatives from Australia, Canada, Chile, Namibia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom published nine proposals within a report, Closing the Net: Stopping Illegal Fishing on the High Seas.

The proposals included specific action steps.

Proposal 1 International *MCS Network

Proposal 2 Global information system on high seas fishing vessels

Proposal 3 Participation in UNFSA and FAO compliance agreement

Proposal 4 Promote better high seas governance

Proposal 5 Adopt and promote guidelines on flag state performance

Proposal 6 Support greater use of port and import measures

Proposal 7 Fill critical gaps in scientific knowledge and assessment

Proposal 8 Address the needs of developing countries

Proposal 9 Promote better use of technological solutions

*International Monitoring, Control and Surveillance (MCS) Network for Fisheries Related Activities (imcsnet.org).

More recently, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the Task Force formed an independent panel of experts to create a governance model for the Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs) to serve as a standard or benchmark for RFMO self-evaluation.

The panel published a set of best practices in 2007 (https://www.oecd.org/sd-roundtable/papersandpublications/39374297.pdf). The impressive document contains the statement that a flag state member of an RFMO should only authorize vessels to fish to the extent that it can effectively exercise its conservation and management responsibilities under UNCLOS, thereby tying compliance ensurance to initial licensing.

Unit 7 Resources in the appendix contains information relevant to IUU Fishing.

Unit 8 will look at how offshore energy leasing works.

Notes

Lewis SG, Boyle M (2017). The Expanding Role of Traceability in Seafood: Tools and Key Initiatives, 82 Journal of Food Science S1, A13 – A21.

Agnew D, Pearce J, Pramod G, Peatman T, Watson R, Beddington JR, Pitcher J (2009). Estimating the Worldwide Extent of Illegal Fishing. PLoS ONE 4(2):e4570. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0004570.

Unit 7 Study Questions

- What conditions contribute to IUU fishing?

- If solving IUU fishing involves addressing those conditions, what kinds of tools are available in addition to law and policy?

- Technology-based solutions to monitoring IUU fishing and intercepting illegal catch are developing rapidly. Are they sufficient alone? Are social and economic interventions necessary?